We all think we will know what to do when the time comes, and there are many times that do come between frailty and ageing and helplessness and death, but we don’t. It is always difficult. Love is not enough. We all need help to know what to do, even what to say.

Aged care is about life and it is about humility.

Humility is a great word because it is an admission that we don’t know everything. That there are some things greater than us and they are quite often life and death. And the why behind it all.

And when it comes to being born and to dying or seeing loved ones die, we have limited control.

When we were children, our parents were our exemplars—they provided grown-up examples of how to grow up. They are still doing this. The difference is that in practical matters, and in matters of care and love, we may now be the ones responsible.

We have joked about this. “Be kind to your children. They will be picking your nursing home.” My youngest daughter has been quite upfront about this since the age of about eight, when she must have already thought her parents were looking old. She said she intended to move us into a nursing home, shortly after we have paid for her Year 12, then put the house in her name, raze it and build something less old. Aren’t kids scamps, sometimes? We told her she would need power of attorney for that, and she showed us how she can already do our signatures.

But the truth is that while we may banter about ageing, it is quite likely that none of us really knows what it actually means. What happens when we become the parents of our parents? What kind of help will they need? How do we help them without making them feel helpless? How can we avoid treating them as if they are helpless?

“Dad! Get off the roof!”

“I know what I’m DOING! Pass up my GLASSES! And also my STICK!” (My dad was, in fact, on the roof just a week after his hip replacement. In case you think that they are only a worry when they are small boys and they are climbing trees.)

And what is required, and how does it change, and how quickly can it change? From a hand on an elbow going up and down the stairs, to a ramp or an inclinator, takes how long?

From talking loudly because getting on means getting deaf, to talking loudly and slowly because getting on means getting slow, doesn’t it?

If the helping hand is curtly brushed aside, if the talking loudly and slowly causes wild offence and bad language, does this just mean that getting on means getting cranky? Or are we being patronising gits, or overprotective children, or helicopter offspring?

Remember when our own children (where applicable) were young, and many of us took quiet pride in our parenting because we spoke to our children “just as if they were adults”, only tiny adults with much more energy than us and a stronger desire to have several puppies? Now we are parenting our parents, perhaps we could treat them as adults also, with greater justification. This is a good starting point.

We must never assume, never presume and isn’t that easy to say? They’re us, only with more years up: that’s the only guideline.

As with everything in life, problems arise when we don’t know what we are doing, when we don’t know the options, when we don’t even know the right questions, let alone the right answers. When we don’t know, as they say, what we don’t know. Why does old age and caring for our elders come as a surprise?

Don’t blame it on the baby boomers. We really didn’t think we’d be forever young. Not even Roger Daltrey, who hoped he’d die before he got old, and who is now in his seventies and in excellent health. Roger’s still touring, too, except that when he starts shoutin’ ’bout his generation his audience shouts back “Speak up!”

Perhaps aged care or even ageing is not discussed enough simply for the same reason death is now called “passing”. Or perhaps “moving forward”. Or some other euphemism. “How’s your dad?” “He’s a euphemism.” “Oh, I am sorry to hear it.”

There are things in life and death that we would rather be out of sight and out of mind. Our old age may be one of them. Other people’s evident old age should not.

Or maybe we just don’t know where to start.

Because our ageing parents often present a complex and emotional and troubling challenge.

And many of us have lost perspective, or at least some grasp of what time is and does, and we regard our elders as some sort of ancient alien species and not as ourselves, God willing, in the decades to come. “Wait! If Mum’s 75, that would make me, what, nearly 45???” Yes, it does, embrace it. If this perspective were restored it would most happily combine true empathy and sympathy, and also naked self-interest. Do-as-you-would-be-done-by would become a long-term retirement plan, and a good one.

So, if it’s coming soon to a parent or parents near you, don’t panic. We all need help to help the older people in our lives. Our parents, for example, and not excluding our grandparents, aunts, uncles and any other elders within the radius of our family, our community, and our affections. They could do with some help, whether we like it or they like it or not.

The practicalities can be bit of a fight, to be frank. Time and time again, in all my interviews, with partners, offspring and professionals, the common cry was: I pity the old person who doesn’t have an advocate, who doesn’t have kids or a trusted person to look after them. To quote one person’s informed outburst, “I mean to try to have a go at the system on your own when you are sick and old. I think about that all the time—if an elderly person tried to manage the systems and bureaucracies and legalities, Centrelink, the medical system, moving into aged care, applying for Home Care Packages, ACAT, it is a whole other language. If they tried to do any of that themselves, they would have no chance, no chance at all.”

You may very well be their number one essential service, because the world is impatient with old people, and very often you are their only defence. There are many people who would exploit their vulnerability and their naiveté and your goodwill and good intentions. They want to pluck those strings that bind you to your parents and play you like a fiddle, they want to manipulate old folks and persuade and entice and rort and gouge and loot, often while seemingly offering sanctuary. Worse, there are some who want to ignore, sideline and neglect. There are even a substantial number of people who want to abuse and confuse and cause angst and anxiety. It is a jungle out there in the world of ageing.

Having said that, there are also lots of support services to help older folk. However, the systems you have to deal with to access this help are so complex and time-consuming and confusing and frustrating, you can feel defeated before you have even spoken to a human.

You need to prepare for what may lie ahead.

As with any journey, you need to know where you are going and what you might expect along the way. What supplies you need, what support you need, what challenges you may face, and whether to pack thermals or a sarong.

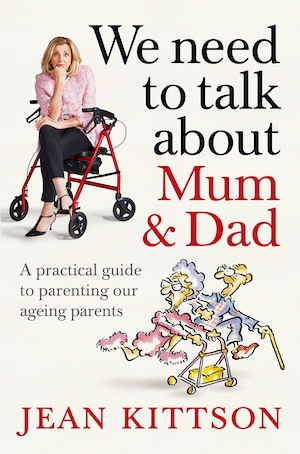

We Need to Talk About Mum and Dad by Jean Kittson. Published by Macmillan Australia, RRP $34.99. Out now.

How helpful was this article?

Click on a star to rate it!

0 / 5. 0

Be the first to rate this post!

Jean Kittson

Related posts

Subscribe

Receive personalised articles from experts and wellness inspiration weekly!