How do you deal with another child being mean to your child? Here are the 6 things you should do—and no, it doesn’t involve in stepping in.

Skills for making friends is one thing, but your child also needs skills for maintaining friendships and resolving conflict. Kids can be inconsiderate and uncharitable—some deliberately, others out of sheer thoughtlessness—so playground run-ins will unfortunately be a reasonably regular occurrence. If your child doesn’t know how to handle conflict, they won’t know what to do when disagreements arise, and their friendships will suffer, along with their confidence.

6 tips for when another kid is mean to yours

It will be upsetting to hear your child talk about any nastiness they’ve been subjected to by other kids, and your distress may well compel you to take matters into your own hands. Don’t. Before you act, pause and take stock.

- Ask questions to help you better understand exactly what’s happened, making sure you ask questions like “What did you do/say before they did/said that?” so you can gauge if your child has contributed to the upsetting events in any way.

- Don’t rely on direct questions like “Are you to blame for any of what happened?” to get you this information because it won’t work. Kids are self-focused thinkers and, without any malicious intent, your child will give you a biased, victim-focused account of events.

- As your child describes what happened to upset them, repeat what you’ve heard so your child can correct any misunderstandings on your part, and as you do, try to stay calm. If you let your emotions get the better of you, your child might feel as if they can’t talk to you when things go wrong—either because they misinterpret your reaction and assume you’re mad at something they’ve done, or because they don’t like to see you upset—and they won’t come to you for help in future. Don’t get too caught up in your own distress. Make your child’s needs your focus.

- When you have a better understanding of what’s happened, show your child you understand by empathising with their distress. Don’t try to show you understand by recounting stories from your own childhood; well-meant as they may be, they’ll frustrate your child and make them feel like you’re making everything about you. Say something like “I bet it was really hurtful and upsetting to hear Peter say that, especially when Alex had just told you that you couldn’t play. It’s not a nice feeling when people say things like that. I’m sorry you’ve had such a rough day.”

- Once your child has had an opportunity to vent and talk about how they feel, look at ways to help. One option is to get involved, but don’t automatically jump to this. Resolving issues on your child’s behalf might help solve things this time, but what about next time?

- Teaching your child skills to navigate social issues independently will mean they’ll feel able to cope in any social situation, no matter what gets thrown their way, so make skills practice your go-to instead.

Mean kids are not necessarily bullies, but bullies can be mean kids. Here’s how to recognise if your child is being bullied and what to do.

2 skills your kid needs to deal with mean kids

There are two skills in particular your child needs in their conflict resolution toolbox: assertiveness skills and social problem-solving skills. As with all social skills, practise is key, so don’t just tell your child what to do: show them.

1. Assertiveness skills

Encouraging your child to stand up for themselves is a start towards boosting their social resilience, but you’ll also need to teach them what being assertive actually means.

If your child’s school-aged, start by explaining that people generally fall into one of three communication categories:

- Passive communicators

- Aggressive communicators

- Assertive communicators.

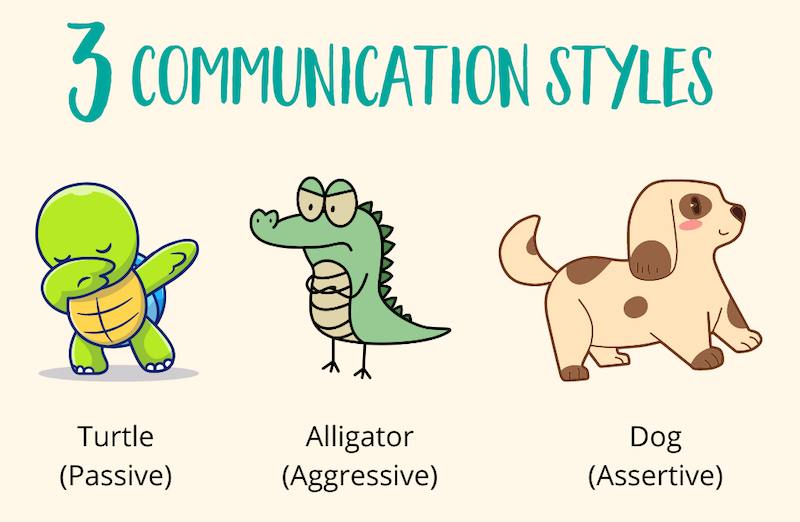

Alternatively, use animal metaphors. For example:

- Passive communicators speak quietly with poor eye contact, don’t like to say no and have trouble standing up for themselves so as to avoid conflict—like turtles, who retreat into their shells when they feel scared or unsafe

- Aggressive communicators stand over people, speak in a loud voice, think their own thoughts and feelings are more important than anyone else’s, and can be scary like an angry alligator

- Assertive communicators say what they think in a straightforward, non-threatening, respectful way, using good eye contact and a confident, calm voice, and they’re equally respectful of their own thoughts and feelings and the thoughts and feelings of others—like dogs.

Use role plays to show your child what each communication style looks like in practice. Pick a few specific scenarios (some examples are listed below) and ask your child to help you act out passive, aggressive and assertive responses for each, making sure you exaggerate actions so the differences between each communication style are clear. As you practise, note which communication style your child is best at because that’s probably their default communication style. If they’re more naturally inclined towards passive or aggressive communication, don’t panic; you can help them practise being assertive.

Role play skills practice

Here are a couple of practice role play ideas. However, role plays are generally most effective when they resemble the scenarios your child is likely to have direct experience with, so use your knowledge of past playground struggles to make up your own role plays as well.

Scenario 1

You’re playing with two friends and they start whispering behind their hands. You ask them what they’re talking about but they won’t tell you. What can you do?

- Example passive response: Keep sitting there while they whisper to each other and don’t say anything else about it.

- Example aggressive response: Walk over to them and rip their hands down to stop them whispering, and yell at them for being rude.

- Example assertive response: In a clear, calm voice with good eye contact, say, “I don’t like that you’re whispering to each other and leaving me out. It’s making me feel upset and I’d like you to stop.”

Scenario 2

Your friends are playing handball but one of the boys is cheating and won’t sit out even though he lost. What can you do?

- Example passive response: Say nothing and let him keep playing even though it means someone else will miss out on a turn.

- Example aggressive response: Walk up to the boy and push him out of his square. Yell at him to get lost.

- Example assertive response: Clearly and calmly say, “Max, you got out, we all saw it. You need to go to the end of the line so other people can have their turn.”

Practising being assertive

If your child finds it hard to be assertive, help them to practise in front of a mirror (videoing practice works just as well) so they can see what they need to do to be more decisive and self-assured in their communication. Have them practise assertive phrases like “I don’t like it when you say nasty things like that, I’d like you to stop calling me names” or “I don’t understand why I can’t play, let’s find a way for me to be part of the game”, so your child has an assertive repertoire to draw on.

If they still need more help, you can shape their assertiveness with constructive feedback, but make sure you balance constructive criticism with positive feedback: “You did such a good job that time using a clear, firm voice! Let’s practise one more time and this time try to look me in the eyes while you say it as well. You’re doing so well.” Limit yourself to one or two key suggestions, so your child doesn’t feel dejected and overwhelmed.

You’ll need to help your child practise being assertive on a regular basis. Coach your child and show them how to be assertive. If you see your child acting non-assertively in a social situation, pull them aside quietly and help them to plan a more assertive response. Similarly, if your child’s upset about something that happened at school, get a blow-by-blow description of what happened, help your child to reflect on whether their response was passive, aggressive or assertive, and if it was a passive or aggressive response ask them to help you role play an assertive response so they know what to do next time.

If your child is five or under, or at school but struggling to grasp the difference between passive, aggressive and assertive communication styles, use more basic descriptions. For example, explain that some people are angry alligators and yell and shout a lot, some people are shy turtles and find other people scary, and other people are confident dogs who stand up for themselves but are still nice to others at the same time.

When your littlie acts like an angry alligator or a shy turtle, pull them aside and help them change their approach. You’ll need to be fairly directive, so don’t ask what they could do differently; tell them what they should do instead. For example, say, “I can see you’re being an angry alligator because Sally won’t let you have a turn with the skipping rope. Let’s practise being a confident dog instead. Go and say ‘Can I have a turn with the skipping rope too?’ and then wait for Sally to finish.”

Assertiveness is a tricky skill, so aim to practise a few times each week, remembering to offer lots of praise and positive reinforcement when your child’s able to ditch their usual passiveness or aggression to respond with confidence instead. While you’re teaching your child to be assertive, be mindful of how you communicate with others, too. Your actions are powerful. If your lessons on assertiveness are intermixed with demonstrations of passiveness or aggression on your part, your actions will overpower what you say, and your child will routinely react with passive or aggressive responses as a result.

If your child continues to react aggressively despite lots of practice and fairly good assertiveness skills, cast a wider net with your skills practice. Your child might have the assertiveness skills to respond effectively, but lack the necessary emotion regulation skills to keep their anger in check, and this might be why you’re running into problems. Continue to practise assertiveness skills but add emotion regulation skills practice into the mix. A combined approach should help your child get back on track.

2. Social problem-solving skills

Your child will face all kinds of issues in the playground. Kids who refuse to play what your child wants to play, kids who are picky about who they “let” play with them and bossy kids who railroad play. Social problem-solving skills are a must to help navigate these issues. Kids younger than six or seven will struggle to learn problem-solving skills in full, so if your child’s younger than this, stick to the age-related adjustments mentioned below.

Being rejected by your peers is a form of social pain that your kids will inevitably experience. In the video below, Collett Smart offers tips on how to help your child through it.

When your child’s upset about something that’s happened at school, get a blow-by-blow description of what’s occurred. Validate your child’s feelings first, then once they’re calm enough, ask them to help you brainstorm possible solutions to their problem. If they can’t think of any ideas, suggest two or three solutions they can pick from, but only do this if your child actually needs you to. If your child’s slow to think of solutions, it’ll be tempting to jump in with your own, but try not to. Your child needs to learn to problem solve, and if you’re too quick at jumping in with your own suggestions, you’ll rob them of the opportunity to learn this skill. Instead, practise social problem-solving more regularly, using both hypothetical and real-life situations. With extra practice, your child will get better at solving their own problems—but only if you let them.

Once you have a list of possible solutions, look at the pros and cons of each, and ask your child to consider whether each solution will help to solve their problem/leave them feeling good about the way they handled themselves/show themselves to others in a positive light.

If your child’s seven or under, they’ll struggle with evaluative thinking like this, so skip these questions and model pros and cons thinking instead so your child understands why certain solutions are better or worse than others. Once your child learns how to evaluate solutions, phase out modelling and revert to asking questions instead (e.g. “If you skip hockey practice to go to Sally’s house instead, what do you think your teammates will think? Can you remember what happened a few weeks ago when Melissa skipped practice to go to the shopping centre? How did people react then?”).

After you’ve looked at the pros and cons of each solution, rule out any solutions that won’t solve your child’s problem or are likely to cause further social issues—your child feeling bad about their actions or hurting someone else, for example—and ask them to choose the solution they think will work best. If their final solution isn’t the one you would pick, resist the urge to take over (unless the idea is appalling) and let your child run with their own idea. Being more directive might lead to a faster resolution this time, but you’ll also block your child from having the experiences needed to learn what works and what doesn’t.

Extracted, with permission, from Parenting Made Simple, by Dr Sarah Hughes (Exisle Publishing, 2020).

How helpful was this article?

Click on a star to rate it!

3 / 5. 2

Be the first to rate this post!

Dr Sarah Hughes

Related posts

Subscribe

Receive personalised articles from experts and wellness inspiration weekly!