Giving kids pocket money isn’t simply about how much or how often. It’s also about teaching kids financial literacy, work ethics and life skills.

In his book, The Barefoot Investor for Families, popular television personality, author and financial adviser Scott Pape—the “Barefoot Investor” himself—says, “Paying pocket money is one of the most powerful tools you have to teach your kids about money.”

In fact, what you do now about their pocket money could help ensure your children don’t grow up with credit card debt plaguing the rest of their working life. Research by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) in 2018 revealed one in six Australians is struggling under a mountain of credit card debt that might never be repaid, with outstanding balances totalling $45 billion.

Simply put, if we aren’t careful, we will raise a generation of children who spend far more than they save; who owe far more than they are ever able to repay. Thankfully, the way to ensure our children grow up with good money management skills is as easy as getting them three glass jars.

When to start giving children pocket money

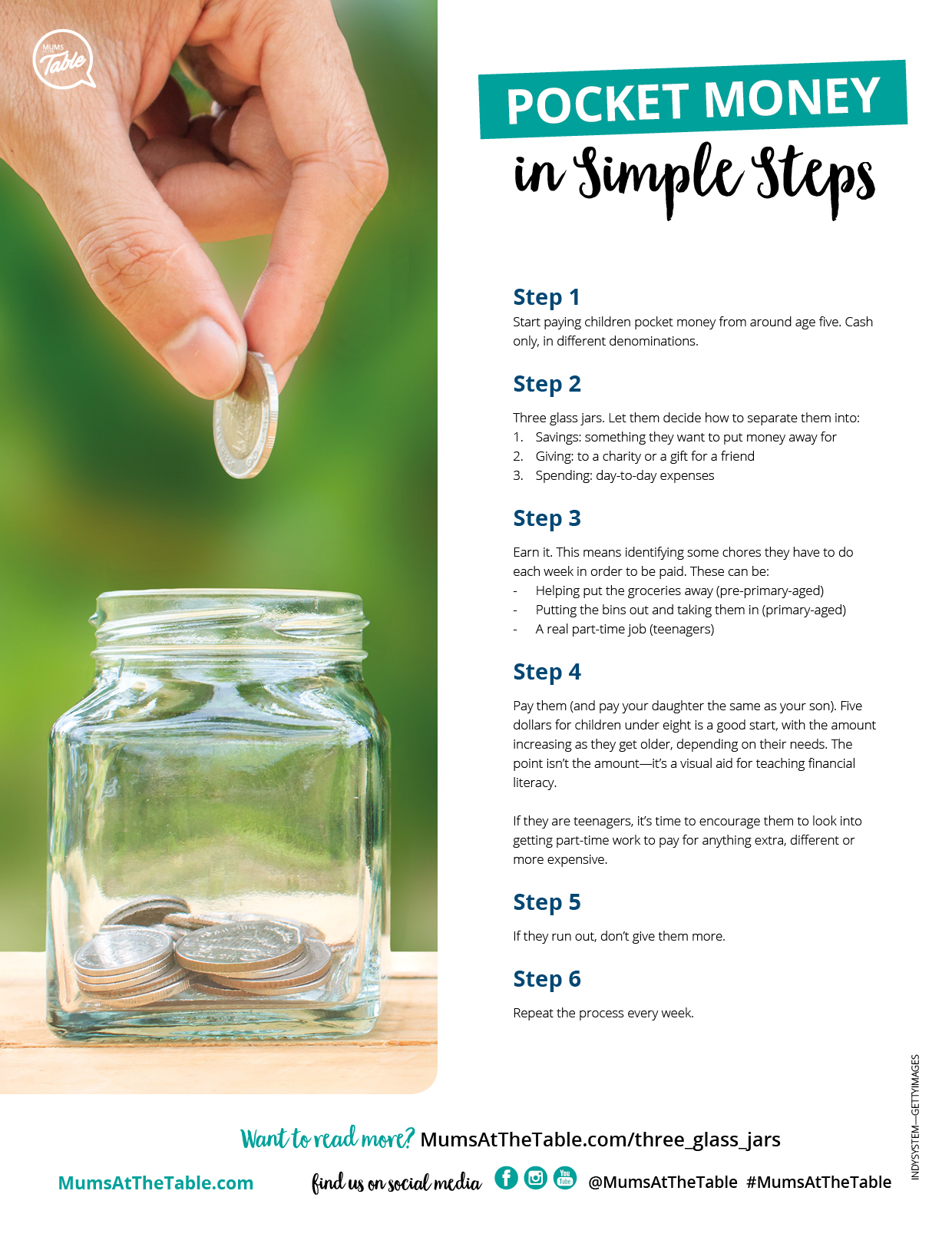

Helen Baker is an author and financial planning expert based in Queensland and her tip on how to teach children financial literacy using pocket money begins with giving them real money: cash. She suggests breaking the money up into smaller denominations, “so a dollar coin, 50s, 20s 10s . . . a range, so they know how much it all adds up to be and that you can break it down”.

This is where the three glass jars come in. “Get them to break the pocket money up between savings—something they want to put money away for; giving—they might want to give to a charity; and spending money,” says Helen. “If they can break up [the money] from what they’ve got, they learn that it doesn’t go into one pool. If you think about bank accounts, if you just have one where everything goes in and everything comes out, you never know whether you’re really saving; there’s no vision for what’s building.”

Read: Teaching kids about money: 8 savvy ways

It’s this sensory aspect of being able to touch and see money that Helen believes is the foundation to teaching children the value of money. “They can physically see what is happening in those jars,” she explains. “They can see it build, they can see it decrease, they can see the amount they can pull out. They get the idea that if they put this money away, they can save for a toy or something that’s important to them. By seeing it, as opposed to using ATM cards, they can have a correlation between the reality and how to manage money.”

Scott is also an advocate of the jar strategy and, as he says in his book, what you’re doing is laying the foundations “and the best way to do that is the old-fashioned way, by seeing the money”. And lest you think the jar strategy is only for young children, think again. Scott even advises it for teenagers. Yes, we’re talking 14-year-olds. “I’m not trying to be cute—research suggests it’s the best way to teach your kids about money,” he asserts in his book.

But when do you start? From an early age. Helen believes a five-year-old isn’t too young to start budgeting their own money. “As soon as kids can start asking for things, I think it’s a really good time to teach them that they cannot have everything they want, because this is how much there is and you have to make choices about what you want.”

What you are trying to do is help them understand the difference between needs and wants, to make choices and decisions, and understand why you can’t have everything that you see.

Household chores and weekly pocket money

Perhaps one of the more controversial aspects of pocket money lies in how—or why—you give it. Should children be earning their keep in the family and be paid for the chores they perform around the house? Or are said chores their responsibility that they’re meant to carry out regardless and pocket money is given simply because they are part of the family?

Helen’s suggestion is a compromise of both schools of thought. “If we are going to teach children about financial literacy, it comes with the attachment that one day they are going to have to work,” she says. “Each family is not going to do it the same way. There are things that you just do as chores because you are part of the family, but the extra bit is teaching them if you do extra, you can get paid for that, which is really how it works in life.”

Want a personalised chore chart for your child?

Click here now!

She suggests letting children understand parental love and responsibility means they don’t have to pay for food or rent, but if there’s a family holiday coming up or if there’s something special they want to spend money on, then “teach them to wash the car or something like that in order to get some money. You’re teaching them what it is like in the real world. We all have to go out and work to generate income in order to live off and at some point, they are all going to have to make that leap. Setting that standard early is good and it helps them understand what Mum and Dad do every day when they go to work.”

The Barefoot Investor for Families recommends a similar compromise, with Scott suggesting giving children just three jobs to do each week in order to earn pocket money.

How much pocket money do you give?

In July last year, a University of Melbourne study revealed when it comes to pocket money, girls were, across the board, paid less than their brothers, and were much more likely to not be paid at all. Similar findings were revealed back in 2016, with boys earning an average amount of $13 a week in pocket money, while girls got $9.60.

It’s a shocking—and sad—revelation at a time when women still have to campaign for equal pay for doing the same job that we’re setting our daughters up for failure at home. So whatever you do and however much it is, pay your children the same amount of pocket money (if they are of similar age).

Helen suggests $5 for children under eight is a good start, with the amount increasing as they get older, depending on their needs. As Scott says, the point isn’t the amount—it’s a visual aid for teaching financial literacy. This means giving them the amount they need (for older children, this may mean something for going to the movies and hanging out with their friends) but expecting them to manage it.

As they get into their teenage years, encourage them to look into getting part-time work to pay for anything extra, different or more expensive.

Helen also suggests paying pocket money weekly because “in a week, you absorb the weekend and the normal week. They can see how they are spending that money.”

The most important thing parents need to know about pocket money, Helen says, is, “If you give them something to spend and if they run out, don’t give them any more because that’s how you teach them to depend on credit cards in the long run. What you are trying to do is help them to make decisions and understand that they will have to make the money last for as long as it is, whether it’s today or the week, and if they make decisions to spend it all at the start of the day or week, then that is their choice. Just tell them to make sure to think about it the next time. We only learn by making a mistake.”

Helen also warns against using debit cards, because while these don’t incur the type of debts credit cards do, they still don’t have the sense of reality that cold, hard cash does. When you are only spending the money in your wallet, “you see how it goes down very quickly”, says Helen.

Debit cards, credit cards, ATM cards and any other form of payment methods can wait until you are confident your children understand money and have some form of financial literacy. In the meantime, get those glass jars out—and good luck!

Read: 4 fun games when kids are learning about money

Stretching pocket money beyond savings goals

There are usually only two aspects of money we think about: saving and spending. However, Helen encourages parents to teach children about a third: giving.

“We’re pretty blessed in Australia and while we can look at people who have more than us, if we look at how many more have less, then we can start to think about how we can give a little bit of something that we have to somebody else and that’s a really good thing,” she says. “But it might not be every parent’s thing, so it’s up to them.”

As Christians, we also believe everything we have comes as a blessing from God. Returning tithe and giving offerings to the church—back to God—is our humble way of showing our gratitude and serves as a reminder that He is our Provider. So teach your children to set aside 10 per cent of their pocket money for God, and encourage them to drop it into the offering bag the next time they are at church.

FREE PRINTABLE!

How helpful was this article?

Click on a star to rate it!

4.8 / 5. 5

Be the first to rate this post!

Melody Tan

Related posts

Subscribe

Receive personalised articles from experts and wellness inspiration weekly!