If you’ve ever struggled with getting your child to do or accomplish anything, you might want to try this tip.

Children are born incompetent. Perhaps a kinder term would be “helpless”. As babies, we do everything for them. As they grow older, we teach them skills to survive while guiding them toward safety.

Our job as parents is to educate our children in the way of life and the easiest way we’ve done it is to tell them.

“Do it like this,” we say, as we instruct a preschooler on how to cut potatoes into even cubes.

“Tidy your room,” we order, along with the many other household chores we expect them to do.

Telling is efficient and effective. The job gets done in the way we want, although maybe not quite in the timeline or thoroughness we expect. Telling also isn’t wrong, especially when we’re dealing with a younger kid.

However, this job of telling starts to fray at its edges as our children get older. Think back to your last interaction with your primary schooler or teen, and chances are, many of the telling would probably fall under the category of “nagging” (to them, at least).

Our children are no longer listening to us. They’re no longer motivated to do anything that may benefit them—homework, chores . . . just being good kids. Who swapped our compliant babies for these monsters?

The 10- to 25-year-old brain

As my son hurtles towards his 10th birthday, I have started to detect changes in his behaviour and attitude. At times, it feels like I already have a sullen teenager in my house.

Turns out, he’s probably on the right trajectory.

“Age 10 roughly corresponds to the start of pubertal maturation, which is biology’s alarm clock for adulthood. Puberty starts a cascade of changes in hormones, the brain, the body and in social life,” writes Dr David Yeager in the book 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People.

Dr David is a developmental psychologist who has done years of studies on adolescent development and how to positively influence young people psychologically.

From around the age of 10 to the rather surprisingly older age of 25, our young people’s behaviour and motivation are very much influenced by two specific things they crave. Understanding this craving and responding to it correctly can change how our children react to us. Even better, it can help us steer them towards positive growth. They may even do their homework without us nagging them to.

The call for independence—and more

“Neuroscientists have shown that during puberty the brain becomes attuned to social status and respect,” Dr David continues in 10 to 25. “This gives our brains cravings for experiences such as pride, admiration and respect, and makes our brains averse to socially painful experiences, such as humiliation and shame.”

In other words, as our children grow, they start to deeply desire acceptance and belonging. They want to know we think they are competent, smart and responsible enough to do things, to do life. They want us to accept them for who they are and that they belong as a valuable and contributing member of the family and society.

Simply telling our children what to do or pointing out their mistakes are surefire ways to ensure they feel humiliated and ashamed—even if we do it gently and kindly.

Dr David cites previous failed attempts to get children to stop smoking as an example. For decades, teen smoking was on the rise in America. Campaigns after campaigns telling young people about the detrimental impact of smoking yielded little results. That was because what these young people were hearing was that adults thought they weren’t smart enough to look after their bodies. Until the “Truth” campaign.

What the “Truth” campaign did was a stellar example of cashing in on young people’s desire for status and respect. The series of advertisements and messaging depicted young people exposing Big Tobacco’s insidious scheme to cause everybody to be addicts. Young people were shown to be intelligent, rebellious and autonomous by choosing to reject cigarettes. It was a huge success. Teen smoking rates dropped.

What parents can do

By the time our children approach 10 years old, we need to keep in mind their deep desire for status and respect in any interaction we have with them. If we want them to do anything, if we want to motivate them, address what they crave and watch the snowball effect.

The principles outlined by Dr David in his book echo that of parenting expert Dr Justin Coulson. In his book, Dr Justin points out that children have three basic psychological needs: Connection, competence and control.

To motivate our children, Dr David suggests using what he calls “collaborative troubleshooting” and adopting a “mentor mindset”. This means while we should set a high standard for them to achieve, we need to work alongside them, first to help them find relevance and purpose for what they’re doing, and then assist them in getting there after we allow them to decide how they are going to do it.

As a mentor, our role is to guide not direct. It’s more:

“I know you can do this maths problem because you are smart. However, there are some concepts I can see you are struggling with, which is why you are stuck. Let’s figure it out together”,

and less:

“You were obviously not paying attention in class, which is why you can’t do this maths problem. Here is what you should have done instead.”

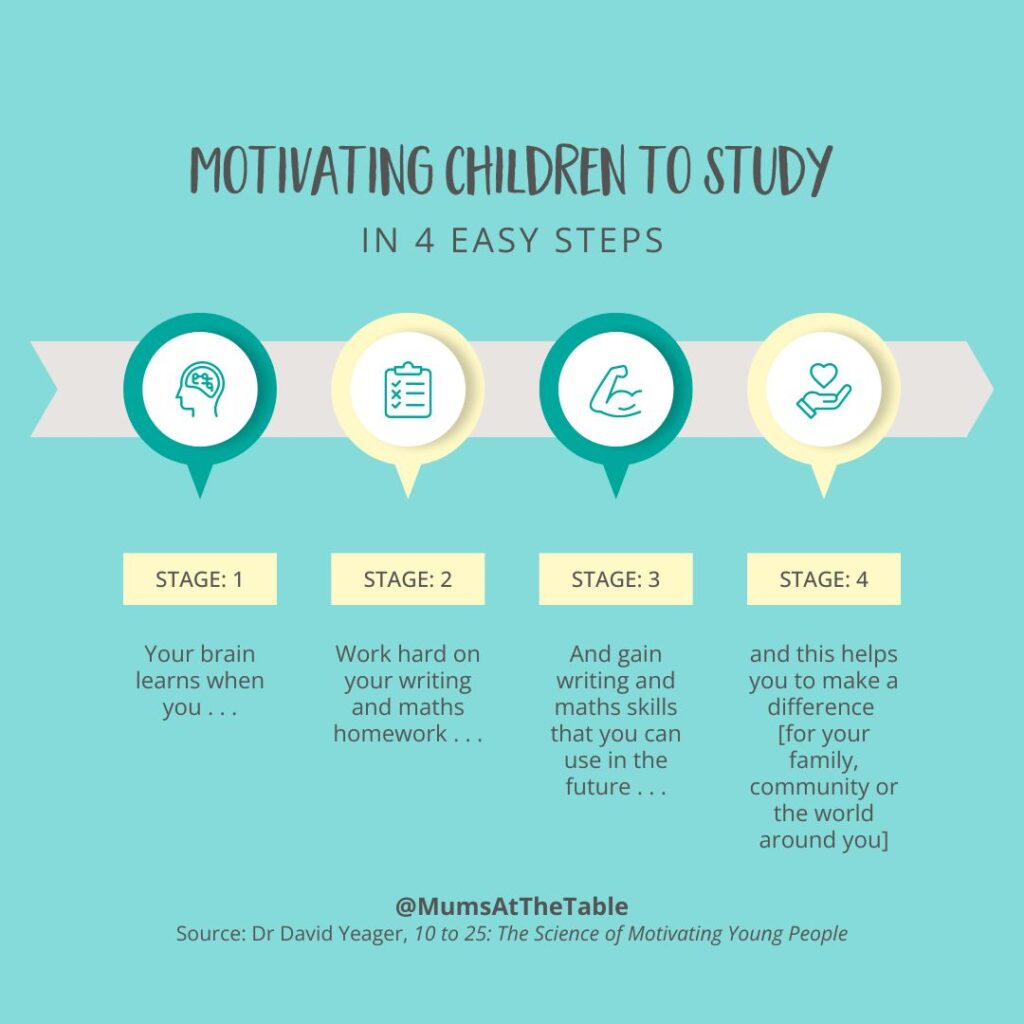

He breaks it down into four simple steps:

- Ask, don’t tell. Avoid grownsplaining (think mansplaining for parents)

- Honour their status, point out their competence and expertise, don’t invoke yours

- Validate their negative feelings and explain why they may feel that way, don’t diminish

- Presume agency

Motivating children to study

Perhaps the most interesting part of Dr David’s book was when he addressed the issue of school, homework and study. As a typical Asian parent, my way of encouraging my son to study hard is to tell him he can “get a good job in the future and make lots of money”.

What Dr David discovered was that such reasons barely serve as motivation for children to work hard. Instead, he argued, they need to be given a higher and better purpose. This meant helping them realise studying can make them more educated, thus giving them the status and respect as someone who has something intelligent to say and therefore make a positive contribution to the world or have the freedom to pick the life they want to live.

“Our experiment showed that if you encourage a meaningful purpose for learning—one that involves both contribution to others and the status and respect one can gain from having stronger skills—then you can motivate young people to show the discipline and hard work that adults usually fail to see when they follow a conventional approach,” Dr David wrote.

Changing their perspective

For the most obstinate of children, Dr David has yet another suggestion. It’s a six-question guide, borrowed from parenting expert Lorena Seidel, that helps our children change their perspective about something, without us telling them to. In other words, six simple questions to ask that helps them to own the answer, instead of us giving it to them (which they probably won’t accept).

As Dr David puts it, “They think, I’m upset because the situation is objectively terrible. They rarely consider, I’m upset because how I’m seeing the situation is a problem, but I could choose to see the situation differently, and that would help me achieve my goals.”

The next time your child rails against something being unfair or declares you hate them because you’ve just said no to them, ask them:

- What does this [what just happened] mean to you?

- How is that meaning making you feel?

- Is that serving your goals?

- What’s something else it could mean?

- How would it make you feel if you thought that?

- Would that serve your goals?

Dr David tried the line of questioning on his six-year-old after his son had a meltdown when his parents refused to buy him a toy. As he details in the book, the questions worked, much to his own surprise.

Even better? Asking these six questions can help our children as much as they can help ourselves.

The verdict on 10 to 25

It’s not every day a book is published that can be applied both in parenting and business. Due to its wide age span, 10 to 25 does just that. It’s a useful book for parents with primary- and high-schoolers and teachers of that age group, but just as important for managers working with young people in their first or second jobs.

As a result, 10 to 25 is not a parenting book per se, in that it does address teachers and managers. The book cites many evidence-based studies and does well in explaining the science. However, it is not an easy read. While not entirely academic, 10 to 25 does lean towards being a scholarly piece.

There are many real-world scenarios and examples that make the book practical. There is even a section at the back filled with activities and questions that you can answer to further develop the strategies and tips shared.

The strategies presented by Dr David in his book show a lot of promise, but they also require a shift in approach and thinking. It won’t be an overnight change and the challenge for parents would be to take the time to ruminate and consider how it may apply in our individual situations. I have found I needed to brainstorm what a “mentor mindset” would be to a specific situation, to the extent of writing down responses.

Fully absorbing the philosophies presented in 10 to 25 to motivate young children will require time and hard work, which many of us time-poor parents will struggle with. However, simply reading the book to glean its principles may be just as helpful, as we try to understand our young people.

Dr David Yeager’s book 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People is available now.

How helpful was this article?

Click on a star to rate it!

0 / 5. 0

Be the first to rate this post!

Melody Tan

Related posts

Subscribe

Receive personalised articles from experts and wellness inspiration weekly!